Share

Related Topics

Tagged As

Many landlords and tenants do not understand why mold problems start and how to safely clean them up when they do. This document is designed to eliminate the confusion by providing simple guidance followed by detailed examples to help prevent the most common problems we have observed responding to hundreds of complaints. (Note: This guidance was written for people living in the northwest USA, and isn't for hot and humid climates.)

We do not strictly control Google ad content. If you believe any Google ad is inappropriate, please email us directly here.

In summary, you need to know that:

- A mold problem is an excess moisture problem

- Excess moisture comes from leaks or condensation

- Leaks are the landlord’s responsibility

- Condensation is the tenant’s responsibility

- Condensation is poorly understood by both parties and is a very common, easily preventable source of mold-causing excess moisture

With a good faith effort by both tenants and landlords, we can keep mold outside, where it belongs.

Mold Guidance for Tenants and Landlords

Figure 1. Condensation from excessive indoor moisture on the window glass drained and ponded on the window sill, soaked into and wicked up the drywall, and provided plenty of moisture to cause the black mold growth visible next to the window.

A mold problem always starts as an excess moisture problem. When mold appears, concerned tenants and landlords often “discuss” who is at fault, who should clean it up and how the cleanup should be done. Responsibility for mold growth usually depends on the cause of excess moisture.

Unwanted Moisture Sources.

There are 3 main ways that water or excessive moisture gets into living spaces to enable the mold growth that should not be allowed to grow indoors:

- Weather leaks from outside (landlord’s responsibility),

- Plumbing leaks inside (landlord’s responsibility), and

- Condensation of moisture from the indoor air onto cool surfaces (tenant’s responsibility).

In the first two cases with actual water leaks, it still falls on the tenant to promptly notify the landlord, preferably in writing, that water is leaking into the unit. The tenant is doing the landlord a favor, trying to prevent damage to the structure, while at the same time defending his or her own health against exposure to the mold that WILL result from leaks that are ignored or fixed too late.

Figure 2. Too much moisture in the air (high relative humidity) leads to unwanted condensation on cool surfaces like double pane windows in cold weather. The moisture drips down, accumulates on sills, and can leak into wall cavities below causing hidden mold growth on wood and paper backed wallboard. Single pane windows will be colder still, resulting in condensation even with normal indoor humidity levels (below 40%) and may require daily drying of sills with towels to prevent mold growth and water damage.

The concept of condensation is very important. Condensation occurs when moisture suspended in the air turns into liquid water on a cool surface. The surface temperature at which this occurs is known as the “dew point” temperature. This is what happens when water beads up on a glass of ice water…that water came from the air. Control dew point temperature by controlling room temperature and relative humidity. More on that a little later…

Chronic excess moisture anywhere in your home will result in mold growth. It’s not magic! Typically every square inch of your home and your belongings are covered with at least a few microscopic mold spores, unavoidably wafted or tracked in from outside, just sitting there, probably not hurting anybody. But add water and mold spores will grow to form visible spots or “colonies” that will continue to grow and enlarge as long as moisture is available.

If indoor airborne moisture (relative humidity) is not controlled and your windows -- especially modern double pane - - are chronically fogged and wet, you will find that this condensation is reaching other cool surfaces as well, encouraging mold growth, for example, on:

- Exterior surfaces starting in the coolest spots like corners and wall/ceiling interfaces because this is where un-insulated wood in the wall provides a “thermal bridge” to the cold exterior (Figures 5 and 6)

- Shoes and other belongings in closets that share an exterior wall

- Furniture placed near cool exterior walls (Figures 3 and 4)

Preventing Condensation, The Short Version

To prevent condensation and resultant mold growth:

- Keep relative humidity below about 40 to 50 percent.

- Control (reduce) relative humidity by using effective bathroom, kitchen, and utility room exhaust fans above common moisture sources. Make sure the clothes dryer is venting properly. Cook with lids and do not dry clothing on indoor clothes lines or racks. Check that exhaust fans are actually moving air: the suction should hold up a tissue.

- Make sure the “used” indoor air gets exchanged daily: Flush the unit aggressively with cold outside air by opening doors and windows for 5 minutes or so; if windy, maybe 60 seconds will do.

- Confirm your safe relative humidity level using a reliable digital gauge. A good relative humidity gauge (called a thermometer/hygrometer) will cost about $25 and this is cheap insurance to protect property and occupant health.

- Use a dehumidifier if necessary.

Figure 3. Mold growth caused by condensation on the cool cabinet placed against an exterior wall in a rental unit. The excessive indoor relative humidity (regularly exceeding 60%) was the culprit. This surface can be cleaned with soapy water.

Figure 4. Condensation: Tenants kept the apartment at 60 degrees, cold enough that the back side of their dresser was below “dew point”, the temperature at which typical moisture levels in the air will condense on a surface. With the dresser chronically wet, mold got started and amplified. This can probably be scrubbed off (outside!) and painted. To prevent a recurrance of the mold, surfaces need to be kept warmer either by increasing the apartment temperature and/or allowing air circulation behind the dresser, or lowering the relative humidity in this space.

Figure 5. Condensation: Mold growth in bedroom corner of exterior wall. The combination of high relative humidity from occupants breathing all night (exhaling water vapor) and the cool surfaces of the exterior wall led to condensation and mold growth.

Figure 6. Condensation: Mold growth on inside surface of exterior door. Again, cold surface meets moist air, gets wet and supports mold growth. This can be washed off and repainted.

Preventing Condensation, The Longer Version

Condensation may be best explained using a very typical cold weather scenario: Three college students move into an apartment that has modern double pane windows and baseboard or wall-mounted electric heat. Baseboard electric heat is expensive, so the students keep the doors and windows shut tight to save money. They might only heat selected rooms.

In a tightly sealed home, moisture accumulates from typically very moist lifestyles: cooking, showering, even simply breathing will add lots of moisture to the air increasing relative humidity well past the desired 30 to 50 percent level.

The first warning sign of excess mold-causing moisture is fog (condensation) on the room side of double pane windows which can drip down to “pond” on sills (Figures 1 and 2). The response to this warning should be to quickly and thoroughly ventilate the unit. By quick, we mean perhaps five minutes…maybe only half a minute with the help of a windy day: open all doors and windows and try to make a “wind tunnel” out of the unit, rapidly flushing the warm wet air out and allowing the cold outside air to come in.

“I paid to heat that warm air!” you might say. True, but the air in your unit only contains about two percent of the heat you bought; 98 percent of the heat you bought is in your stuff, your furniture, and the warmed surfaces of the unit. And that “stuff” will not release its heat during the brief required flush out.

Now close your doors and windows and allow the room air to warm up, which it will do quickly because there is not much substance to air…it is easy to heat and cool. When the colder outside air is brought inside and warmed up, its relative humidity is also lowered making this fresh air a powerful drying force in your unit. The moisture on your windows will evaporate into the dry room air; watch the fog retreat from your windows, hopefully never to return.

Let’s try another example: Picture yourself standing in what you know is a too wet apartment that you need to flush with outside air to dry out. But looking outside, it is 40 degrees, raining cats and dogs and it’s foggy (100 percent relative humidity = saturated air = the air is completely full of moisture so you can actually see the excess = fog). Why in the world would you want to bring all that moisture into your apartment if the goal is to dry it out? Good question…here’s the answer. Forty degree fog will become quite dry air (32 percent relative humidity) just by warming it up to 70 degrees. It’s just physics, the laws of nature. Raise the temperature of air and you will lower the relative humidity and dew point, every time, as demonstrated on a ‘psychrometric chart’ (check it out online). Repeat the flush out as necessary to keep the unit’s relative humidity under 50 percent, in general, during the colder months.

Why is this moisture so good at finding cold spots on which to condense? In nature, moisture wants to move from more to less (e.g., evaporation) and from warm to cold (leading to condensation). This is why a dehumidifier works: It creates a zone of very low relative humidity and coolness at the machine that acts like a cool and dry magnet, harvesting moisture out of the air, converting it to a liquid that can go down the drain and out of the home.

Other Factors Impacting Condensation

Figure 7. Standing water in a crawlspace: 40 percent of the air you breathe can come from the crawlspace, pulled up by the force of warm air rising. Excess crawlspace moisture is bad for your health, bad for the structure, and a significant factor driving relative humidity UP upstairs.

Standing water in a crawlspace under a building is nothing but trouble for landlords and tenants. This water is constantly evaporating, adding unplanned moisture to the air upstairs in the living area, making it that much more difficult to keep relative humidity under control. When a crawlspace is as wet as Figure 7, this evaporative water vapor often passes through the house with the force of warm air rising until it reaches the cold underside of roof sheathing and condenses, leading to attic mold growth (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Condensation: Mold growing on roof "sheathing" in an attic. In winter months, moisture (water vapor) leaking through the ceiling of the living area with the force of warm air rising will condense on the cold attic sheathing, causing property damage and mold exposure to occupants. Left uncorrected, the roof will fail and need replacement.

Leaks from Weather or Plumbing

Figure 9. Plumbing leak: Prompt communication with a landlord could have prevented this damage.

Leaks are generally the landlord’s responsibility. Of course the landlord typically won’t know about a new leak unless informed by the tenant. The sooner a tenant notifies the landlord of a leak, the less likely surfaces will stay wet long enough to grow mold. Mold can get started in a couple days, so, you know, don’t delay. We won’t discuss fixing the source of leaks; just emphasize the hazards of delaying response to leaks.

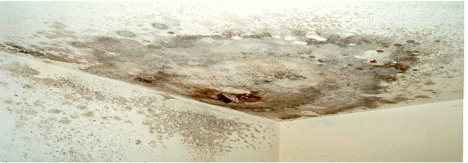

Figure 10. Leak from roof or plumbing: Left unrepaired, a small leak can become a big problem. This wallboard must be removed using personal protection and a plastic enclosure under negative pressure exhausted to outside to prevent further contamination of occupant property. The ceiling and wall cavities will also be moldy and need careful cleaning by protected workers.

A very common mistake made by landlords even after successfully stopping a leak is failing to fully realize the scope of the resulting moisture penetration into building materials (Figure 11). Typically, drywall, carpet, padding, and subfloors get wet from a bad leak. These materials must be aggressively dried to prevent mold growth, sometimes requiring professional assistance. Carpets may need to be lifted to rapidly dry the carpet, pad, and floor boards using dehumidifiers and fans. Drywall may need some holes drilled through it to get dehumidified air into the wall cavities to get things dry before mold gets started. The alternative, commonly, is mold growth, occupant exposure and property damage that will need more careful repair with mold contamination as a complicating factor (Figure 12).

Figure 11. Plumbing leak: Hot water tank leaked and was replaced, but wallboard is still sopping wet (meter says 32.6; 28 is very wet) and mold will grow. This is where a moisture meter comes in very handy; finding damp materials adjacent to a leak before mold grows saves time and money for landlords…the meter may well “pay for itself.” This wet drywall, IF it can be saved, needs to be opened and aggressively dried using professional dehumidification techniques.

Here is an example of missed moisture following a plumbing leak: Let’s say a hot water tank leaks and soaks surrounding carpet for a couple days before it gets noticed. The landlord gets the water heater replaced and, in good faith, authorizes aggressive drying of the carpet and pad. But the adjacent drywall has wicked up some moisture that can’t be obviously noticed without a moisture-sensing meter (Figure 11). Saturated drywall WILL get moldy (Figure 12). The best solution for do-it-yourselfers is to use a moisture meter to test the walls and ensure they are below 16 percent or so. Above 18 percent moisture content, drywall will typically support mold growth.

Figure 12. Saturated wallboard must be aggressively dried or mold WILL grow, often on the hidden paper backside of the wallboard in the wall cavity. This moldy wallboard should be carefully abated using a negative pressure enclosure and respiratory protection for workers.

Controlling Bathroom Moisture

Some bathrooms have no exhaust fans. Others have fans that don’t work or are so noisy occupants don’t want to use them. New exhaust fans are available for about $175. These new fans are incredibly quiet, long-lasting, and very energy efficient. In fact these fans can use a lot less energy than a compact fluorescent light bulb! A bathroom with no exhaust fan is very challenging to keep free of mold growth.

Safe Mold Cleanup in Rental Properties

Cleanup of incidental mold growth may be a simple matter of misting the mold with soapy water and washing it off a surface. However, extensive mold growth, like a slow leak in a wall cavity involving several square feet of mold growth, usually requires workers who are trained to erect plastic sheeted enclosures around the work area to prevent release of mold to contaminate the whole rental. In addition, exhaust fans should be used to “depressurize” the work zone so airflow moves from the clean rental into the enclosed work zone and then outside.

Figure 13. Drywall covered with mold needs to be carefully removed. Painting over mold is not acceptable work practice.

All too often, we see unprotected workers cut out mold-covered drywall that they then haul through the rental to the dumpster with no precautions whatsoever to prevent spores released in the process from contaminating the occupants’ belongings.

The article, Mold Remediation in Occupied Homes, contains straightforward guidance applicable to most situations.

Contact Northwest Clean Air Agency (NWCAA) if you have questions.

HHI Error Correction Policy

HHI is committed to accuracy of content and correcting information that is incomplete or inaccurate. With our broad scope of coverage of healthful indoor environments, and desire to rapidly publish info to benefit the community, mistakes are inevitable. HHI has established an error correction policy to welcome corrections or enhancements to our information. Please help us improve the quality of our content by contacting allen@healthyhouseinstitute.com with corrections or suggestions for improvement. Each contact will receive a respectful reply.

The Healthy House Institute (HHI), a for-profit educational LLC, provides the information on HealthyHouseInstitute.com as a free service to the public. The intent is to disseminate accurate, verified and science-based information on creating healthy home environments.

While an effort is made to ensure the quality of the content and credibility of sources listed on this site, HHI provides no warranty - expressed or implied - and assumes no legal liability for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed on or in conjunction with the site. The views and opinions of the authors or originators expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of HHI: its principals, executives, Board members, advisors or affiliates.